54 to Danville

What follows in these posts are somewhat random memories of my childhood until I was a young adult at about age twenty-three. I’ve only told brief bits and pieces of this story to close friends and family, my husband and adult kids, because it was just too painful to remember. But one thing I have learned is that uncovered pain, your “unspoken broken” as Ann Voskamp says, doesn’t heal and you can’t use it until you talk about it. You can’t heal, forgive, move on from what you don’t reveal. So eventually these stories will come together like puzzle pieces being fitted to reveal a beautiful picture, a picture that God alone already knew He was painting. I can’t leave out the pieces I don’t like or don’t want to deal with anymore than you can leave a piece out of a 1000 piece puzzle, because it leaves a hole, scarring the finished product.

It’s difficult to sort out what is the result of my childhood imagination and fears, what really happened that night and what I was told happened that night. I think my fragile heart started building a wall of protection that night. All the activity and the chaos around me played like a drive-in-movie during a rainstorm. Like the windshield was clouded with rain and the picture was blurry. It was a defense mechanism that I would use for protection for most of my life.

The farmhouse we lived in was large or at least to me it was. It had a small closet-like pantry. Not like what we would call a pantry today. It was more of a small kitchen with a sink, cabinets and small appliances. The stove, refrigerator and dining table were in a much larger room off of that pantry. The table was one of those metal-50s-era ones with a yellow Formica top and chairs upholstered in sticky yellow plastic.

That night, we were standing in the kitchen, facing the door. My mom, my brother, Steve, and me. To the right of the door were coat hooks lined up across the wall bearing the barn coats and hats my dad used. Even though he rarely interacted with us kids, my dad’s presence was enormous. He was a big man, a troubled man whose life seemed to be spinning out of control. I didn’t know what was wrong but I sensed something was horribly wrong.

After my dad stormed out to the barn, mom quickly hustled us out the door, to the small back porch. We needed to go down to Missy Dye’s house, mom informed us. It was really Mrs. Dye but my brother and I either couldn’t say “Mrs.” or thought it was “Missy,” so that’s what we always called her. Mr. and Mrs. Dye were an older couple just a few hundred yards down the road. At the time it was a dirt road. Cars always going too fast would leave a trail of dust and gravel flying behind them as they sped up and down the road.

Mr. and Mrs. Dye were grandparent types, kind of on the scary side. They were nice but Mr. Dye’s weathered, wrinkled face just wasn’t friendly or inviting. He smoked a cigar. His face looked like he could never quite get it clean. Had a gravely voice. Always carried a black lunch pail to and from the factory he worked at. He wore navy blue pants and a navy work shirt with “Fulmer” stamped on the left pocket. Fulmer was his name. My dad would later work at that same factory, have a black lunch pail and ride to work with Mr. Dye.

Mrs. Dye was small in stature and was missing the thumb and first two fingers from her right hand. Chopped off in a lawn mower accident is what mom told us. Mrs. Dye, while mowing her lawn with a gas powered rotary push lawnmower had reached under the lawn mower to see why the blade had stopped and stalled the engine. Whatever she did caused the blade to suddenly start spinning again, before she could pull her hand out. Mom heard her screams and ran to her aide when it happened. Mom found the severed digits and sent them with Mrs. Dye in the ambulance but they couldn’t be reattached so Mrs. Dye learned to do everything with missing fingers. That’s the hand that I always picture when I think of her. I don’t remember the other hand. She always had gingersnap cookies when Steve and I came to the house. She handed them to us with the missing-fingers hand.

We ended up that evening standing behind Mr. and Mrs. Dye’s house, the side of the house opposite the dirt road. We were to stay out of sight. Mr. and Mrs. Dye didn’t want us to go in the house in case my dad came. I don’t think they wanted to deal with dad being in their house or have him think they were hiding us. Still not sure what was going on but I heard mom say, “Paul has a gun.”

Paul was my dad.

He was the youngest of eight siblings. He was born and raised on the farm where we were living at the time. He had never really left home. My dad’s two oldest siblings were boys and then there were five girls, then my dad. Mom always said dad was not wanted, that he was an “accident.” She said Grandma Moser never had much time for dad so he spent most of his time out in the barn with his dad, doing barn chores and tending the farm.

Dad always had guns around.

The night we went to Mr. and Mrs Dye’s house my mom had called Grandma Moser, my dad’s mom, and told her she needed help with dad and to come quick with help. Grandma Moser lived about one mile away from our farm. When she received my mom’s call she called my dad’s siblings for help. My dad always blamed his mother for all his problems. My cousin Ruthann and another cousin Karen (Uncle Byron’s daughter) were dropped off at Grandma Moser’s house, so they were out of harms way while their parents dealt with my dad. Dad’s siblings told their mother not to let dad in if he came there as from what they were hearing he was angry. My grandfather Moser had already passed away so my Grandmother Moser lived alone in a small house off Route 54.

After my dad came back to the house from the barn and realized my mom and us kids were missing he went berserk. We could hear him screaming out for our mom. “Maxine! Maxine!” he yelled over and over. Dad owned a 1951 Hudson, dusty green in color with tan cloth seats. That old green Hudson came flying down the dirt road past Mr. and Mrs. Dye’s house with dust and gravel spewing behind it.

Dad went straight to his mom’s house and pounded on the door, yelling for her to open the door. Grandma Moser had told my cousins Ruthann and Karen to go hide in the back bedroom. Grandma called through the door to her youngest son to go away and go home, that he was sick and needed help. Furious, my dad got back in his Hudson to leave his mother’s house but the car wouldn’t start. Dad got out and pushed the car until he could hop in and pop the clutch to get it to start. He pushed that huge Hudson all by himself, uphill! Then he sped back home. Again, as we stood outside Mr. and Mrs. Dye’s house, the Hudson flew back up the dirt road, a green streak with dust and gravel hurling behind it.

Again we heard dad yelling for my mom. By this time my mom had called her own mom and sister who lived about 20 miles away. Soon all dad’s brothers and brother-in-laws, some of whom he had no affection for, showed up to try to calm him down and reason with him. He was in no frame of mind to be reasoned with. There was Uncle Byron, Uncle Harold, Uncle Rohr, Uncle Deemer, Uncle Bud and Uncle Bill. Dad’s sister Alberta had already passed away during childbirth so there were only six siblings left, besides my dad.

Cousin Ruthann said her mother Marion told her that it took eleven men, including police and ambulance crew to wrestle and subdue my dad and get him in a straight jacket. He wasn’t about to go willingly. This was the late 1950’s or very early 1960’s when you could commit someone to a mental institution against their will. But I think even today rescue crews would have taken him in because he was a threat to himself and others. Dad was hauled off to Danville State Hospital in Danville, Pennsylvania.

I’m considered a “senior citizen” (just barely though) and all my children are adults, most with children of their own, so why am I reading a parenting book?

I’m considered a “senior citizen” (just barely though) and all my children are adults, most with children of their own, so why am I reading a parenting book?

My childhood family was dysfunctional due to mental illness. I often felt alone. Unloved. It caused me to do a lot of things I regret. Some of the consequences of those poor choices can never be removed. But they can be used. We don’t have to hide that brokeness. God can take even the broken pieces of our life and make something beautiful out of it. I didn’t know Jesus then. But today I believe He was there watching over me. Taking care of me.

My childhood family was dysfunctional due to mental illness. I often felt alone. Unloved. It caused me to do a lot of things I regret. Some of the consequences of those poor choices can never be removed. But they can be used. We don’t have to hide that brokeness. God can take even the broken pieces of our life and make something beautiful out of it. I didn’t know Jesus then. But today I believe He was there watching over me. Taking care of me. Mr. Mathias was my highschool history teacher. I was a good student and enjoyed his classes. He didn’t see me as someone who made bad choices or someone who had made one too many mistakes. He could see past that fact and see me for what I might become and he went out of his way to do even one small thing that would be an encouragement. He went out of His way to find out my birthday and plan something special for me. He didn’t have to do that.

Mr. Mathias was my highschool history teacher. I was a good student and enjoyed his classes. He didn’t see me as someone who made bad choices or someone who had made one too many mistakes. He could see past that fact and see me for what I might become and he went out of his way to do even one small thing that would be an encouragement. He went out of His way to find out my birthday and plan something special for me. He didn’t have to do that.

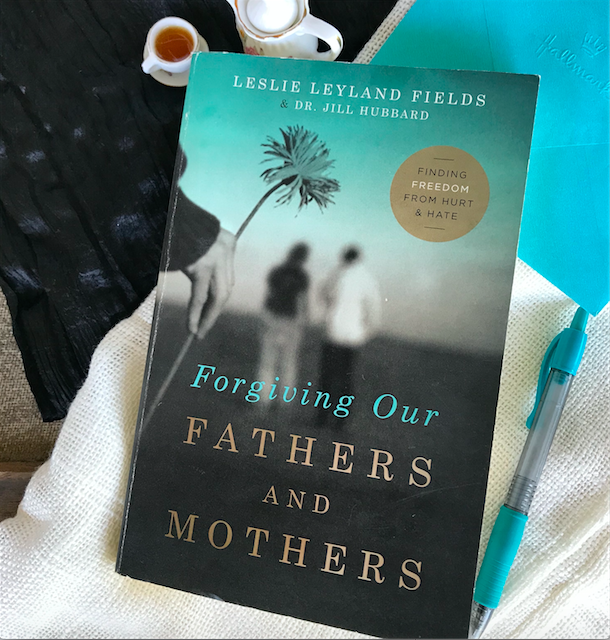

My parents were in the grip of mental illness. Both of them, often at the same time. They were trying to make their way without resources. And when I realized God was present with me through those childhood years and He still intends to use if for good not only in my life but in the lives of others, I can run towards forgiveness rather than away from it. Forgiveness is my ticket out of a self-made prison.

My parents were in the grip of mental illness. Both of them, often at the same time. They were trying to make their way without resources. And when I realized God was present with me through those childhood years and He still intends to use if for good not only in my life but in the lives of others, I can run towards forgiveness rather than away from it. Forgiveness is my ticket out of a self-made prison.